Being traditional pastoralists

with a nomadic bent, the Maasai have used the sprawling grasslands and forested

slopes of the Serengeti National Park, Tsavo National Park and Mkomazi Game

Reserve as a grazing ground for their cattle, which provide them with the milk,

meat and blood they need to survive.

But lately, these rich lands have

also lured many outsiders, including large-scale hunting companies, threatening the

traditional Maasai way of living.

Ancient Maasai culture in the

modern world

Ancient Maasai culture in the

modern world  Saving the Maasai

lands

Saving the Maasai

lands  Empowering Maasai's

women

Empowering Maasai's

women

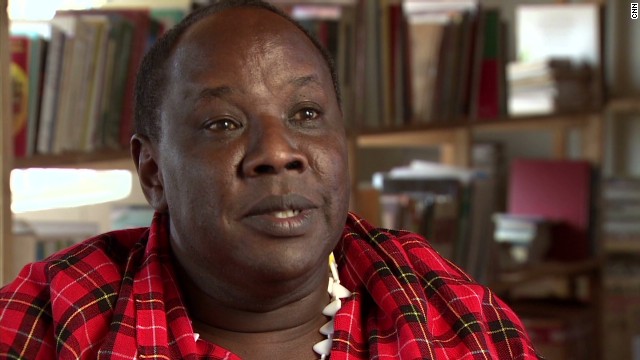

"The riches and the wealth that

come out of it is actually flying away from Maasai land by the rich

and powerful

people," says Martin Saning'o Kariongi, with a wry smile. "Maasai land is a very

rich country, or rich region, but the owners, the inhabitants, are amongst the

poorest in the world. It's very sad but that's the reality."

Aware of the precarious position

his tribe finds itself in, Kariongi, a well-respected Maasai community leader,

has made it his life's work to save his people and their way of life, whilst

helping them adapt to a changing world.

As one of the few of his

generation to make it through high school and further education, Kariongi

started his work as a social development activist in the early 1990s, after

spending time studying in Europe. Upon his return to Tanzania, he organized a

legal campaign opposing a government-forced eviction of Maasai people from the

country's Simanjiro plains.

The High Court of Tanzania ruled

in favor of the Maasai and soon Kariongi was working to improve the economic

conditions of his people too.

"Around 2000 we started to think

that despite the whole struggle for land rights and human rights of the Maasai

people, poverty is growing and so many of our young people are rushing into

cities," recalls Kariongi. "That's when we actually said we have to find a way

to create opportunities for community economic empowerment."

Generations come and go, and each generation puts its own firewood on the

fire and the fire is the culture.

Kariongi's first idea for

self-sustainability was to turn the resources available to the Maasai -- their

animals and abundant milk -- into an opportunity to create wealth for his

people.

Working together with a SHGW, a

Dutch NGO dedicated to promoting sustainable development in rural regions of the

developing world, they launched a company and established five small milk

processing units in five locations around the Maasai plains.

From milking the herds to

processing the milk and producing the dairy products, the business is run

entirely by women. The units can process up to 2,000 liters a day, making

cheese, yoghurt, butter and ghee.

"We started the milk processing

plant as one way of finding a ready market for the women," says Kariongi, who's

based his social development plan on gender equality. "As an economic project

that will create a market where women can sell milk and engage in a cash

economy," he adds.

"It has been going on now for

the last five years and the life of the people, the life of the families have

changed dramatically and women are making so much money."

Today, the company has grown to

include many arms, from an energy and water firm, to a media house producing

broadcasts tailored for the Maasai, to a community ranch that helps improve

access to quality breeds.

They are all growing

organically, based on a strict business model.

"The social investor who is

investing in us is investing as an investor, not as a donor," explains Kariongi,

who is a strong opponent of handouts. "This social business mentality is

actually creating opportunities to awaken our entrepreneurial nature; that we

use our own locally available resources to create wealth and to create

sustainability within ourselves to come out of poverty, rather than depending on

aid," he says.

Read this: Good African Coffee wants trade, not aid

It's all part of Kariongi's

determination to help his people adapt, intact, to the 21st century and avoid

extinction.

"We have created facilities here

-- the radio station, the milk processing plant, the energy and water company,

the internet, the library -- all these facilities to bring modern life to

people, so they don't have to rush to towns," says Kariongi.

"When we lost our

sons and daughters, rushed into towns, our women going to towns, then our lands

will become empty and we might end up in an extinction."

He adds: "Culture is not static;

culture is dynamic, it grows; it's like a fire -- In order for the fire to keep

on burning and giving light and heat, somebody has to be putting new fire wood.

And the culture is like that -- so generations come and go, and each generation

puts its own firewood on the fire and the fire is the culture."

Martin Saning'o Kariongi

(right), a respected Maasai elder in northern Tanzania, has made it his life's

mission to save his people's way of life whilst helping them adapt to a changing

world.

Martin Saning'o Kariongi

(right), a respected Maasai elder in northern Tanzania, has made it his life's

mission to save his people's way of life whilst helping them adapt to a changing

world.

Whether

it's promoting education, encouraging gender education or setting up profitable

businesses, Kariongi is determined to promote self-sustainability within the

Maasai of northern Tanzania.

Whether

it's promoting education, encouraging gender education or setting up profitable

businesses, Kariongi is determined to promote self-sustainability within the

Maasai of northern Tanzania.

Kariongi

has started IOPA, a community-based venture company to help improve the economic

conditions of his people.

Kariongi

has started IOPA, a community-based venture company to help improve the economic

conditions of his people.

The group

has established a women-run milk processing company that's producing dairy

products, such as cheese, yoghurt, butter and ghee. "It has been going on now

for the last five years and the life of the people, the life of the families,

have changed dramatically and women are making so much money," says

Kariongi.

The group

has established a women-run milk processing company that's producing dairy

products, such as cheese, yoghurt, butter and ghee. "It has been going on now

for the last five years and the life of the people, the life of the families,

have changed dramatically and women are making so much money," says

Kariongi.

It's also

established several other companies, including a media house that is producing

radio programs specifically catering to Maasai listeners.

It's also

established several other companies, including a media house that is producing

radio programs specifically catering to Maasai listeners.

"We have

created facilities here -- the radio station, the milk processing plant, the

energy and water company, the internet, the library -- all these facilities to

bring modern life to people, so they don't have to rush to towns," says

Kariongi.

"We have

created facilities here -- the radio station, the milk processing plant, the

energy and water company, the internet, the library -- all these facilities to

bring modern life to people, so they don't have to rush to towns," says

Kariongi.

One of

the most culturally distinct tribes of Africa, the Maasai move around in bands,

grazing their cattle in the rich grassland plains of East Africa they've been

calling home for centuries.

For centuries, the lush national parks of southern

Kenya and northern Tanzania have been called home by the Maasai, one of Africa's

most culturally district tribes.

One of

the most culturally distinct tribes of Africa, the Maasai move around in bands,

grazing their cattle in the rich grassland plains of East Africa they've been

calling home for centuries.

For centuries, the lush national parks of southern

Kenya and northern Tanzania have been called home by the Maasai, one of Africa's

most culturally district tribes.